It is not easy at all to choose a couple of songs from Trịnh Công Sơn for any list of ten songs about the Vietnam War. The first of his five albums in the Sing for the Vietnamese Country series – Hát Cho Quê Hương Việt Nam – is a masterpiece that must be listened from top to bottom. It is not a surprise that both of my selections come from that album.

Hãy Sống Giùm Tôi – Live for Me or Please Live For Me – is perhaps the simplest composition in the entire album: musically, perhaps; linguistically, definitely. It took me, what, all of six or seven minutes to translate the lyrics – half of the time on two or three lines.

Here is the list so far:

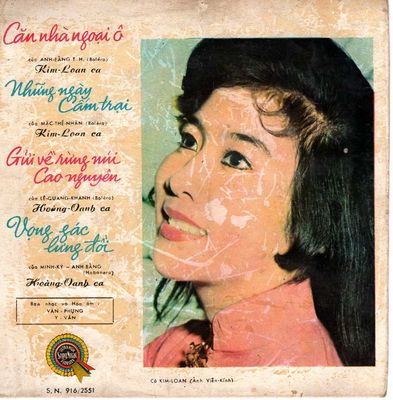

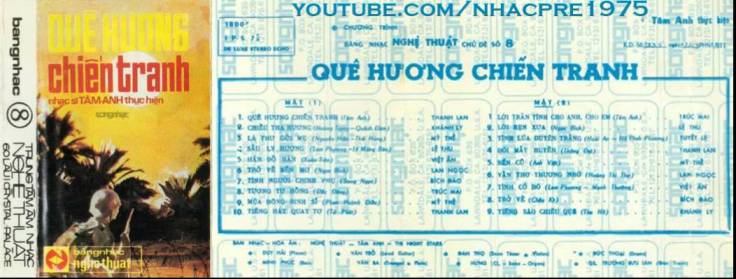

10. Quê Hương Chiến Tranh

9. Tám Nẻo Đường Thành

8. Đưa Em Về Quê Hương

7. Đó! Quê Hương Tôi!

6. Tình Thiên Thu của Nguyễn Thị Mộng Thường

The toughest choice for me is the fifth one. It didn’t take me long to settle on the songs above – or the fourth, third, second, and top songs. (Two of the top five belong to Trịnh Công Sơn; can you guess which songs?) For the fifth spot, I wanted to continue on the theme of romantic love and loss from selection #6. I thought of several possibilities.

Of the ten songs on this list, this is the only one that tells a story: a true ballad. It is based on a true story, now told in slightly different versions, about two young lovers in South Vietnam: Phạm Thái and Nguyễn Thị Mộng Thường. Because of its personal nature and the artistry of the lyrics and melody, this ballad has been very popular among Vietnamese. One should always be cautious with comparisons, but I am inclined to think of it as the Vietnamese equivalent of “Where Do I Begin,” the theme song of the movie Love Story that came out two or three years earlier.

Of the eight or nine composers in this compilation of mine – I’m still debating between two songs by two different authors – Vĩnh Điện is by far the least known. An officer in the South Vietnamese military, he was, I believe, many years younger than the other songwriters on my list. [Correction: He was in fact older than Trần Thiện Thanh – see comment below from Jason Gibbs.] His output in the Republican South was modest, as fewer than ten songs were recorded before 1975. My favorite is Vết Thương Sỏi Đá, “The Heavy Wound,” which has to do with the pain of romantic love than suffering from warfare. Check it out, below or from the website that bears its author’s name.

Imprisoned in reeducation camps for many years after the war, Vĩnh Điện came to the U.S. late in life and, out of his searing experience of prison, brought out a lot of new music. Some of these songs were composed in captivity: as the case with poets and songwriters in the same situation, he kept them in his head. Other songs were written in America. They have been recorded in a dozen of CDs, and you can read about them in this write-up of more than 150 pages!

I set out a few basic criteria in the making of this compilation. One is no more than two songs from the same composer. One is to seek a wide variety on style and content. A third is to limit selections to the period of the Second Indochina War. There were many songs written during or shortly after the French War, and I hope to address the connection between the two periods at some point. But ten isn’t a large number by any means, and leaving out music from the First Indochina War hopefully helps to tighten the coherence of the list.

Another criterion is that the selections come from musicians associated in a significant way to the Republican Saigon, thus leaving out music from North Vietnam and the National Liberation Front (NLF). Communist music is worthy of studies for its propaganda value, yes, but possibly more. But it is not included on this list because it diverges too far from music of the Republican South.

A good case can be made for this song to be ranked higher than the ninth spot, maybe even in the top five. But I’m going to keep it in this spot because it provides a sort of continuity from the #10 song, Quê Hương Chiến Tranh or Country At War.

The title means eight urban roads or ways. While nẻo đường is used enough in writing and speaking, it isn’t clear why Hoài Linh, author of the song, chose eight instead of four, six, or nine – all of which have the same accent tone as eight in Vietnamese, which is dấu sắc. In an online analysis last year, Cao Đức Tuấn makes the argument that the phrase tám nẻo đường thành is particular to the city of Saigon. He suggests an association to the old octagonal Citadel of Saigon – Thành Bát Quái – constructed in the late eighteenth century with crucial engineering assistance from French allies to the first Nguyễn emperor Gia Long. The evidence on this particular point is thin. But the larger point that the title refers to Saigon is plausible, if for other pieces of evidence in the lyrics.

Thinking about this list of “top ten Vietnamese songs of war,” I’ve had the hardest time with the songs in the middle of the list. But I knew exactly which song to begin the series and which one to end it.

For a starter, it is hard to find a better tune than Quê Hương Chiến Tranh – Country At War – if only for the title. Few titles in South Vietnamese music on war are as succinct or straightforward as this one, for it names the most significant experiences among twentieth-century Vietnamese: war and nation.

Bài lời Việt theo sau bài tiếng Anh. Hai bài hao hao nội dung nhưng không giống hẳn. The Vietnamese portion follows the English. I cater each language to different readers and they aren’t entirely the same.

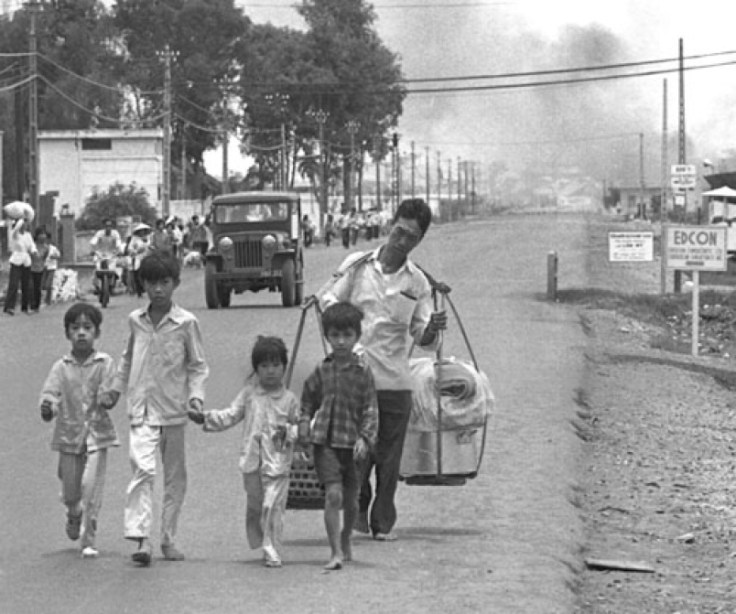

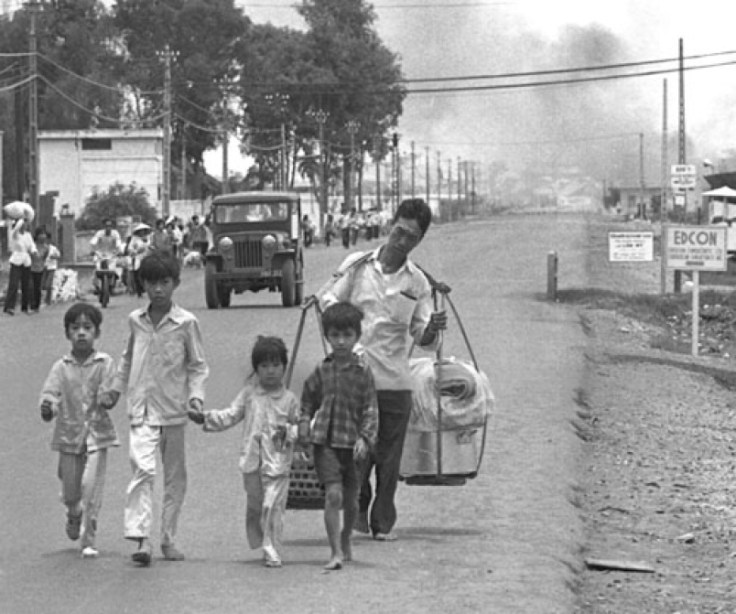

April 30 was of course the climax of the fortieth anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War and the beginning of mass Vietnamese migration to the U.S. But there’s still a lot of the anniversary year left.

Tomorrow is the first day of classes at my institution, and I will continue to honor this anniversary by posting about Vietnamese music related to war and refugees throughout the fall semester and into the spring semester.

You must be logged in to post a comment.