Source: University of Nebraska Medical Center website

Following the fall of Saigon, the majority of 125,000 Vietnamese refugees in the US had to work in jobs and positions very different from their old ones in South Vietnam. A survey in 1977 showed that over 30% of the adult refugees had worked at the “professional” level before 1975, but only 7% in the US. Conversely, the percentage of laborers in crafts more than doubled from 14.3% in South Vietnam to 29.5% in the US.

There were, however, two groups that were more or less able to resume their trades. (Christian clergy might have constituted a third group. But I am leaving them out, Catholic priests and Protestant ministers, because their numbers were small and their occupations might be “professional” in classification but they really belonged to a different category.) First were fishermen, who were often Catholic and northern Vietnamese in origin. They had moved to southern Vietnam after the Geneva Conference and resettled in coastal villages and towns, only to be escape to the US two decades later and resettled in the Gulf Coast. From Texas to Florida, many of them, possibly most, entered the shrimping industry. Their stories, especially conflicts with the KKK, occasionally made national news during the 1970s and 1980s.

The other group came from the opposite side of the occupational spectrum: physicians. They were more mixed in regional origin and religious affiliation. While their newsworthiness was usually limited to local rather national reports, their beginning in the US was just as fascinating as the beginning of the fishermen, if in entirely different ways.

To appreciate this portion of Vietnamese American history, we need to understand the broader context of the health profession, medical care, and physicians in the US during the 1960s and 1970s. In the mid-1960s, the number of physicians stood at 289,000 while their ratio to the general population was 149 doctors for every 100,000 Americans. This ratio was definitely higher than the ratio in 1940, which was 133 doctors per 100,000 people. But it wasn’t much different from the ratio in the 1950s.

Shortage was in the mind of many people in healthcare. Even in the late 1940s, warnings and predictions about shortage of physicians were occasionally issued by important people in the medical establishment. In 1948, for example, the US surgeon general issued a projection that there would be a shortage of 30,000 to 50,000 physicians by 1960. Well, the 1960s saw more frequent calls (and louder) to raise the number of practicing physicians in America. In the realm of popular culture, hospital dramas began to appear on all three major television networks by the early 1960s: ABC, CBS, NBC. Those dramas contributed to the growing expectations regarding health care among the masses of middle-class viewers.

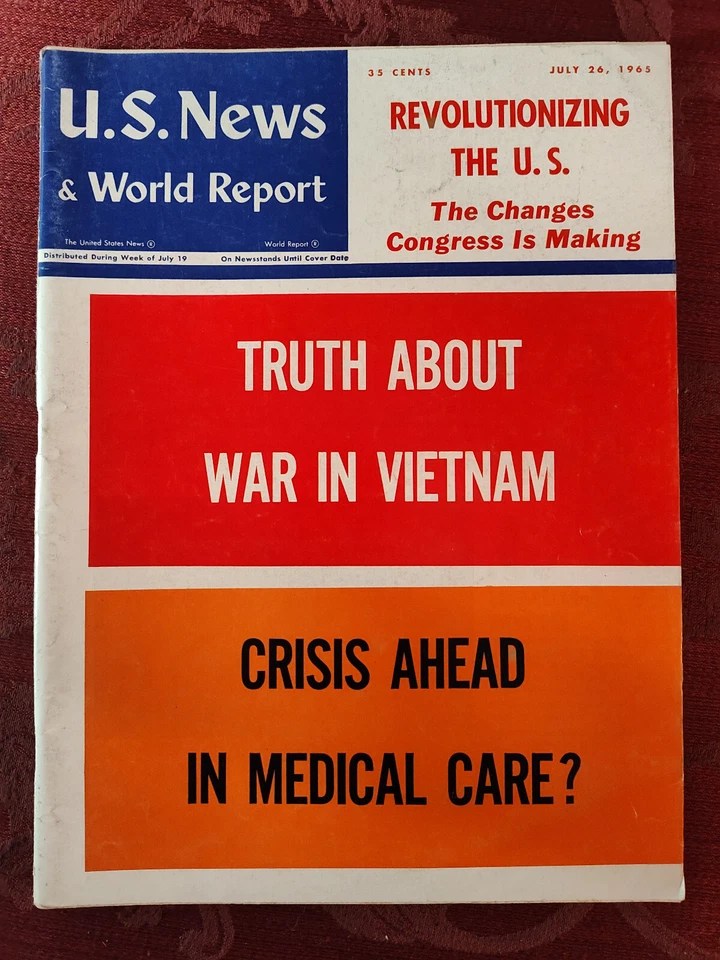

In comparison to TV drama, news coverage about changes and developments in health care was nowhere as much as it is today. It was a big deal when health care made national news. Here is an example of “big news” about healthcare.

In 1965, the weekly U.S. News and World Report asked on the cover of a summer issue whether there was a “crisis ahead in medical care?” The question stood below a headline on the Vietnam War. A major reason for this question was the Medicare and Medicaid Act, which Lyndon Johnson signed into law on July 30, 1965. There was a fear that the new law would flood hospitals with patients, especially elderly ones, staying for up to 60 days thanks to government subsidies. The fear of shortage wasn’t only about physicians, but also about nurses and spaces to accommodate the new and potential demands.

The shortage of physicians was partially a result of little growth of enrollment in medical schools between 1920 and 1960. Most acute were the shortage in rural areas, but the situation wasn’t good either in inner cities. The shortages in rural areas and inner cities were partially an outcome of the Flexner Report in 1919, which was commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation. To quote from a 2017 article in the journal Family Medicine, the Flexner Report

significantly impacted medical education. One of its major effects was the redistribution of medical education from small geographically dispersed programs throughout America to an urbanized university-centered model of education. This fundamental shift had the unintended consequence of worsening the geographic maldistribution of physicians away from rural areas of the country. Furthermore, poor and minority populations living in urban areas did not benefit from the increased physician supply and often lacked access to adequate health care services. Poor, inner city residents were often viewed as “good teaching cases” in these hospital settings, and little attention was paid to their need for ongoing comprehensive primary care.

The last three words in the quotation above indicates a related issue: a growing shift towards sub-specialization that in turn caused a shortage of primary care physicians. The trend towards sub-specialization had already been around for a very long time, but it was getting a lot worse when it was combined to growing demands for physicians. I am not knowledgeable enough, but I gather that it was a massive concern for leaders in the medical establishment.

Responding to these long-term effects, the American Medical Association (AMA) created the Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education in 1962 and commissioned this group to conduct a new study. Published in 1966, the study, commonly called the Millis Report, found several reasons for the shortage of primary care physicians. A second study, called the Willard Report, was also commissioned by the AMA and published in 1966. It made a number of recommendations, which were adapted by different institutions in varying degrees. Since the late 1960s, there would be more medical programs and the number of students attending medical schools would rise.

There is one more aspect about the big picture before we get back to the Vietnamese: physicians who came to the US from other countries before 1975. During the 1960s and well into the 1970s, the needs for health care workers had prompted the US to allow the migration of many physicians, nurses, and others with desirable skills. Now, the migration of skilled workers from a developing country to a developed country was hardly exclusive to the US. Canada, for example, admitted 12,000 people legally known as International Medical Graduates between 1961 and 1975. Across the Atlantic, the UK saw a somewhat higher number of physicians entering from other countries (albeit not Ireland) between 1966 and 1974.

Many more foreign physicians came to to the US, whose government allowed the migration of over 60,000 medical graduates between 1963 and 1979. One reason was the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which favored foreigners with desirable skills, especially in STEM. There had been foreign physicians prior to 1965, but their numbers would grow in the years after.

Among those 60,000-plus physicians were the refugees from the former Republic of Vietnam. I haven’t gotten hold of a precise number, but the best estimate looks to be 425. As suggested by the national context, they quickly became a very desirable group of people for American society and economy.

How desirable? As early as two weeks after the fall of Saigon, the chairman of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand wrote to the White House and urged officials to get Vietnamese physicians out of the refugee camps soon for training and licensing. The doctors at Camp Pendleton and other processing centers, he wrote, “need to be identified [and] some of the ordinary red tape [should be] fractionated so that they can get out of these camps and into some kind of a program which will have an end-point.”

As a result of such advocacy, federal and local assistance to the refugee physicians was swift and abundant. Here are a few examples.

- In southern California, Loma Linda University and Medical Center, which had close ties with the medical establishment in the Republic of Vietnam, welcomed over 400 refugees who had been health workers, including a number of physicians, and their family members. and helped to train them for jobs in healthcare.

- Merely weeks after the fall of Saigon, residents of the village Sutherland in central Nebraska set up a residence for the family of two refugee physicians who were married to each other. It was a happy occasion because the small town had not had a resident doctor for three years. A write-up about them and this community was published in Time magazine, which however did not yet know that Sutherland was one of 19 communities in Nebraska that participated in this program and, eventually, brought in 30 physicians (and their families). After a period to improve their English, the refugee physicians took a special curriculum designed by the College of Medicine at University of Nebraska. The refugees would then take the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) examination in order to be certified and licensed for practice. Medical instruction began in July 1975 and ended nine months later.

- Nebraska was not the only state with a shortage of physicians in rural areas. Arkansas, which long had a need for more primary care providers in rural areas, happened to host a processing center at Fort Chaffee. The governor commissioned the dean of the College of Medicine at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences to recruit refugee physicians for rural Arkansas. Twenty physicians from Fort Chaffee were selected for this purpose. In August and September, most moved to Little Rock with their families and began a curriculum to help them pass the ECFMG exam.

- In northeastern Texas, seven refugee physicians, six men and one woman (who was married to one of the men), were sponsored to four small towns near the Red River. In 1976, they attended a program at Oklahoma University for credentialization to practice medicine.

These examples illustrate the high interest among the American medical establishment to get refugee physicians into practice as soon as possible. They were not legally immigrants but refugees. Yet their skills made them just as desirable as some of their peers who had migrated from India, Taiwan, South Korea, and other countries.

Ironically, the winds began to go the other direction in the 1980s. In 1976, or just one year after the arrival of the refugee physicians, the federal government commissioned another study about physicians. Released in 1981, this report, which didn’t carry a personal name but was known by its abbreviation GMENAC, put forth a “surplus narrative” in the near future. It called instead for a smaller enrollment of medical schools in the US as well as a curtailment of foreign physicians. Not only there wasn’t a “surplus,” but the report unwittingly contributed to an ongoing shortage of physicians in the present.

Leave a comment