Five years ago, Liam Kelley published on his blog a post about Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920-1945 by David Marr. The main reason was the then-recent digitization and online availability of thousands of Vietnamese-language texts from the same period kept at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF). Marr’s book was based on many of those texts that he examined in person back in the 1970s. Kelley acknowledged the encyclopedic nature of this book–and I’d say that specialists in modern Vietnamese history would concur with him. But he also faulted it for simplifying and, ultimately, being completely wrong about discussions and debates on Confucianism during the late colonial era. Kelley wrote,

From my own research, I’m well aware that Vietnam fully participated in the “traditional” world of East Asian culture, and that the ideas of the “traditional” Vietnamese elite transformed in the early twentieth century in ways that mirrored the ideas of their counterparts in other areas of East Asia. As such, one can’t really understand the intellectual changes of the 1920s and 1930s in Vietnam, without an appreciation for the changes that were taking place in the larger East Asian world of which Vietnam was a part. However, that world is largely absent in Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, and that has long troubled me.

https://leminhkhai.wordpress.com/2020/09/18/the-east-asian-modern-vietnam-thats-waiting-for-researchers-in-paris/?

The BnF’s digitization availed most texts cited in Marr’s book to the world at large. Kelley gave a close look at one of the “Confucian texts” that Marr cited and interpreted to be “traditionalist” that was, presumably, put “on trial” by “non-traditionalists.” Kelley demonstrated that this book, entitled Đông Phương Lý Tưởng (Eastern Ideals) was no traditionalist text and that its author, Nguyễn Duy Tinh, was no Confucianist reactionary against the threats posed by modernity. Rather, Tinh’s preface and other contents reveal that he employed modern lexicon and ideas in translating and commenting on some 200 selected passages from Confucian classics. Kelley ended the post by encouraging others to check out these texts and discover more about the “East Asian modern Vietnam” of that period.

I’m not investigating this topic because (a) I don’t know Chinese or the Chinese-based chữ nho; and (b) my interest is the more familiar subject of Westernization advocated by Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh, Tự Lực Văn Đoàn, and many others. I recently found out, however, that a new monograph, Confucian Iconoclasm by Philippe Major, turns upside down the long-standing contrast between May Fourth radicalism and Confucian conservatism in China. It argues that modern Confucianism was another form of iconoclasm. To make his case, Major analyzes two core texts: Liang Shuming’s Eastern and Western Cultures and Their Philosophies (1921) and Xiong Shili’s New Treatise on the Uniqueness of Consciousness (1932). In Major’s interpretative hands, modern Confucianists were hardly conservative or traditionalist, but in fact participated in a “politics of antitradition” by engaging a transhistorical approach to Confucianism. (The book is open access here.)

In addition, I knew that noncommunist intellectuals in South Vietnam were respectful of “traditional” knowledge and wisdom even as they promoted application of “modern” Western ideas to the Vietnamese society and individual lives. Like Nguyễn Duy Tinh, they thought ideas from the “old learning” could be altered and adapted. Some even believed that it was essential to combine “old” Eastern and “new” Western ideas. An example is the book series Học Làm Người (Learning to be human), which was enormously popular in South Vietnam during 1950-1975. (See Chapter 4 of my dissertation about this series.) It was therefore something of a surprise that Marr made this sizable misinterpretation in his excellent monograph. It isn’t the only misinterpretation of the book, but it’s among the biggest.

In any event, the majority of Vietnamese-language books in my possession are digitized copies, but I also have some physical copies on my bookshelves, including a few on “Eastern ideals” or the Old Learning. One title, which was published in two volumes, is Cổ Học Tinh Hoa [Essences of the Old Learning]. It is a collection of some 250 passages from a variety of Chinese classics such as the Analects, the Liezi (Liệt Tử in Vietnamese), and the Zhoushu (Chu Thư). First published in 1925, or six years before Nguyễn Duy Tinh’s book, this collection was authored by Nguyễn Văn Ngọc (1890-1942) and Trần Lê Nhân (1877-1975).

In his youth, Nguyễn Văn Ngọc was educated in both Chinese classics and Western studies. He graduated from the College of Interpreters then worked as a school inspector (thanh tra) for the government. He was also a member of the organization Khai Trí Tiến Đức, or l’Association pour la Formation Intellectuelle et Morale des Annamites headed by Phạm Quỳnh; and participated in the composition of instructional texts on morality for school children. Following the publication of Cổ Học Tinh Hoa, he published a different collection called Đông Tây Ngụ Ngôn [Fables from East and West]. In the 1930s, he participated in the Buddhist Revival in northern Vietnam. Put it another way, Nguyễn Văn Ngọc was actively involved in the modernization of Vietnam, which was a complex development with many different routes and directions. He was no “traditionalist” leave alone a reactionary against modernity and modernization.

Older but lesser known than his co-author, Trần Lê Nhân was educated in the “old learning” then held a series of positions in the colonial educational system. He climbed the ladder as a commissioner of education from the prefecture level (huấn đạo) to the district level (giáo thụ) to the provincial level (đốc học). Perhaps he met Nguyễn Văn Ngọc through his work in the educational system? He, too, contributed to the Buddhist Revival by publishing in Buddhist journals.

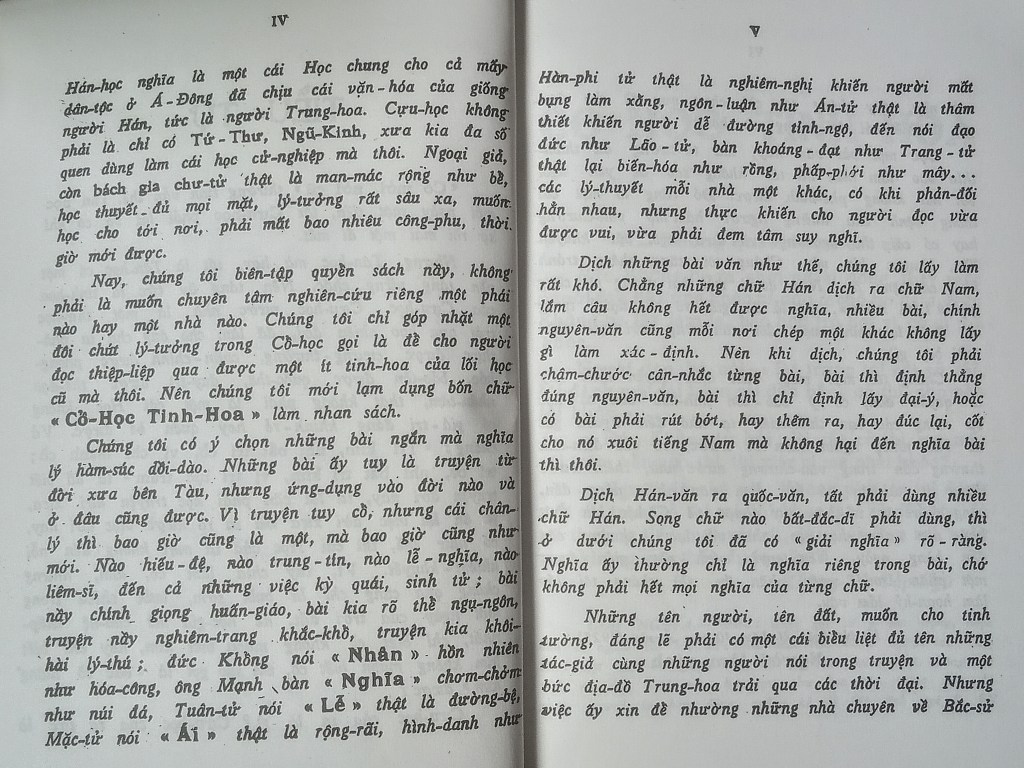

Prefaces are telling, and the preface of Cổ Học Tinh Hoa was no exception. Here is the first of four pages:

My translation of the first ten or eleven lines:

Having the new means attaching the old [to it]. The New Learning is making steady progress while the Old Learning necessarily retreats and, one fears, may possibly disappear one day.

If the New Learning has been appealing [to educated Vietnamese], it means that the New Learning has a firm foundation. That foundation is but the essence of the Old Learning. The Old Learning of our country had gone over generation after generation, helping our predecessors apply for the sake of strength, adjust for the sake of reform, protect our national dignity, and maintain humane values. It is not the sort of low and despicable learning, or the sort of learning to be forgotten about…

From the bottom of the first page and into the second page, the authors further expanded the meaning of Old Learning. This learning for them wasn’t only the Four Books and Five Classics (tứ thư ngũ kinh) that made up the core Confucian texts and that were studied in depth for national examination to the mandarinate. Others, and they named the Hundred Schools of Thought (Bách Gia Chư Tử), were equally important.

Nguyễn Văn Ngọc and Trần Lê Nhân made the case for rediscovering the richness of the Old Learning by naming a bunch of thinkers and ideas on the second and third pages. The Old Learning, they argued, consisted not only “humanity” for Confucius, “rightness” for Mencius, and “ritual” for Xunzi. There are also “universal love” for Mozi ̣(who was the first major rival of Confucius), the legalism in the text of Ha Fei, the ethics and way of Laozi, and the breadth of thoughts in Chuangzi. (I couldn’t figure out who was Án Tử near the top of the third page. Is it a typo?)

Indirectly, perhaps, the co-authors were breaking away from the constraints of Confucianism for purposes of the imperial examination and the mandarinate. Old Learning, they stated by implication, was a whole lot more than the longstanding micro-focus on the Four Books and Five Classics. Vietnamese, they suggested, should widen their understanding of “old learning,” and this collection, like Nguyễn Duy Tinh’s later collection, could be used as a starter to help educated Vietnamese modernize. Even the Four Books and Five Classics should be read with fresh eyes for new insights towards modernization.

On the third page of the preface, they further stated that they may sometimes resort to some old terminology and therefore they would annotate each excerpt. In other words, they were in no way denying the usefulness of the quốc ngữ but they wanted to clarify certain terms with annotation. It’s a perfect example of updating the “old” as a way of contributing to modernization drive by the “new.”

As seen in the photo below, their preface ended with a hope for the “preservation of essences of the old learning.” It may sounds reactionary–and here one could see why David Marr had thought people like these authors to be “traditionalist” in opposition to modernization. But it is in fact a call to renew and relearn the “old” in order to make a contribution to the “modern.”

Historians of modern Vietnam have long recognized David Marr’s fastitious labor in the research and writing of Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920-1945. Since the 1990s, however, most if not all have faulted Marr’s teleological approach in interpreting that putting “tradition on trial” led the communist-led Việt Minh to be the central inheritors of the Vietnamese revolution. Since the 1990s, numerous historians have demonstrated that it was a deeply flawed and wrong-headed thesis, and that Hồ Chí Minh and the Indochinese Communist Party (ICP) might have become the most lasting party but they were only one party among many.

Now, I’d go further and wonder if the title Vietnamese Tradition on Trial is a misnomer or, worse, a massive interpretative error. Was “tradition” really “on trial”? Indeed, was it even “tradition” by the 1920s, leave alone the 1930s and the early 1940s? Or was it a competition in the search for modernity and Vietnamese modernization? Marr’s book remains an outstanding model for deep and laborious research in intellectual history. But it also exemplifies how badly one could be off when one was intent on an interpretative path that allowed too much of an antiwar position to dictate the reading of those hundreds of texts kept at the BnF.

Leave a comment