Books in history and, more generally, the humanities are held in much higher regard than articles, and it’s part of my job to read a lot of them. But I generally prefer reading articles over books. One reason is that articles allow for a feel about subject matters beyond your field. Another reason is that it doesn’t take as much time to read them as you do books. (AI, of course, may eventually change all that.)

I recently went over five such articles on early modern Acadian history, nineteenth-century American Catholic history, and modern Chinese history:

- Nicole Gilhuis, “Colonial Ghosts in Indigenous-British Conflict: A Revisiting of Two 1726 Piracy Trials,” Acadiensis 53.1 (2024).

- Catherine O’Donnell, “‘A Dreadful Wolf Loose in the Fold of Christ’: St. Peter’s Parish, Manhattan, 1806,” American Catholic Studies 134.3 (Fall 2023).

- ______, “‘Ten Thousand Pardons’: Accusations of Clerical Misconduct in St. Peter’s Parish, 1806–1809,” American Catholic Studies 143.4 (Winter 2023).

- Peter E. Hamilton, “‘The Book Which Increases the Human Efficiency’: Taylorism and the Origins of Modern China’s Ideal of ‘Scientific Management‘,” Journal of Asian Studies 83.2 (May 2024).

- Qiang Zhang, “Rehabilitating Republican China: Historical Memory, National Identity and Regime Legitimacy in the Post-Mao Era,” The China Quarterly (2024).

The first article comes from my Pepperdine colleague Nicole Gilhuis, who teaches in the History program. Acadian Studies and Vietnamese Studies are very far apart from each other, but I felt a slight and odd affinity to the topic of her article: piracy trials in eighteenth-century Boston that revealed the complexities of cultural identities, especially people of mixed ancestry, Mi’kmaq and French. This article was the first that I heard of the concept “spaces of power” (attributed to the Canadian historian Elizabeth Mancke). It was nice, too, to see the lasting power of Richard White’s “middle ground” positively referenced in the article.

Gilhuis’ main argument has to do with identity and belonging. The scholarship of the trials in the title had viewed the handful of men of European ancestry to have belonged to cultural France. Her reading of primary sources, however, led to a more nuanced interpretation: that those Acadian men moved into the Mi’kmaw community and became its members. As she argues.

Determinations of community belonging should not be assumed from lineage, patriarch, or even the identity of their 21st-century descendants; rather, they should reflect the dynamic choices of the women and men who moved between colonial and Indigenous communities in 18th-century Acadia.

Some figures in this story eventually became “colonial ghosts,” whom Gilhuis defines to be:

individuals who entered colonial spaces via the channels of empire (settler colonialism, trade, imperial warfare) and once in this new territory moved into Indigenous communities and networks, effectively disappearing from colonial records.

This concept may carry certain affinities to the colonial history of modern Vietnam. In the case of Indochina, however, the “ghosts” tended to be the colonized themselves, who moved to other parts of the French imperial networks–for reasons of labor, exile, incarceration, or something else–only to have disappeared in the records at some point. Lorraine Paterson, for instance, has studied Vietnamese who were exiled to other parts of the French Empire and found that “their stories trace threads of ‘punitive mobility’ that are not reflected at all in the colonial archival record.” For another example, Shawn McHale (GWU) has discovered at least Vietnamese at a Nazi concentration camps during World War II. In other words, they were a different type of ghosts than the men in North America.

The next two articles shared an identical topic: the only Catholic parish in early nineteenth-century Manhattan. It’s because their author is the same person. I applaud the editors of American Catholic Studies for their decision to publish Catherine O’Donnell (Arizona State University) in back-to-back issues. It’s like watching The Godfather and The Godfather II: even though each could be viewed separately, you gotta watch both movies–or read both articles–to appreciate it all.

The focus is on clerical misconduct at the parish level, and most information is about priests and the powerful Archbishop John Carroll, who was overseeing the lone diocese in the U.S. (With the Louisiana Purchase, the diocese suddenly doubled in size, which helped to explain the massive correspondence between the priests and Carroll.) Nonetheless, there are important people, especially a couple of women, who were crucial to the story at one point only to disappear from available archival records before the story reaches its conclusion. Like the Acadians and Vietnamese, they were another kind of ghosts, albeit not colonial ones.

The women were crucial because the priest at St. Peter’s was alleged and accused of inappropriate romantic or sexual behavior towards them. While St. Peter’s once claimed among its members a most illustrious Catholic by the name of Elizabeth Seton, the majority of its female members, who were crucial in voluntary labor to the running of a parish, were more or less invisible. One of them, whose first name was Nancy, didn’t even have her last name in the available records. Although the bulk of these articles is about the priests and Archbishop Carroll, O’Donnell makes sure that both articles end with the women.

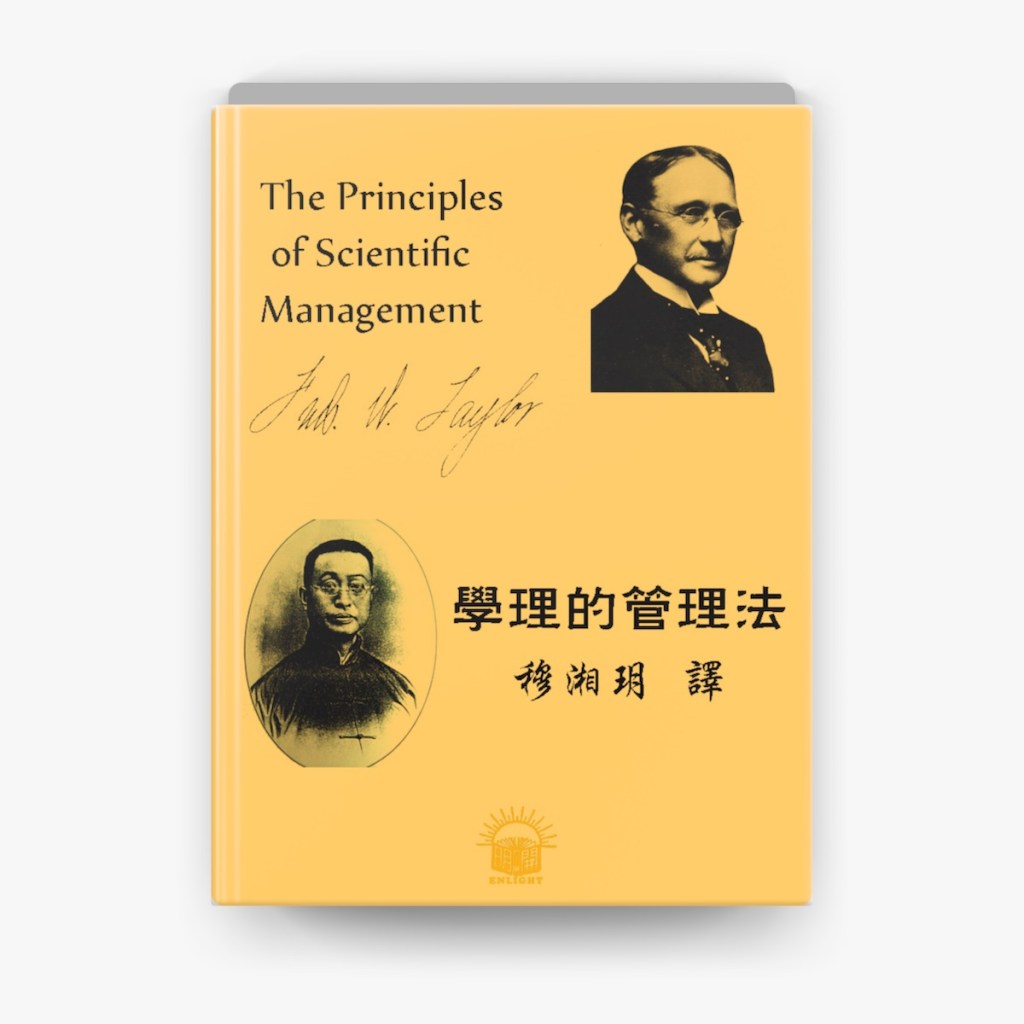

With the last two articles, we shift from North America in the 18th and early 19th centuries to modern China in the 20th and the 21st centuries. Not Vietnam studies, but a touch closer. It’s especially true of the article by Peter Hamilton, a faculty at University of Bristol. The article is about the very influential book The Principles of Scientific Management by the American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor. First published in 1911, this book received widespread interest across the globe. Here’s the gist of Hamilton’s argument:

While most historians regard management as a niche of business history, I approach management as a central technology of modernity due to its intrinsic role in the daily operation of virtually every state bureaucracy, health-care system, university, mine, factory, mill, bank, power plant, railroad, large-scale farm, and civil engineering project. As I will argue, early Republican Chinese intellectuals immediately appreciated this wide-ranging relevance, and by 1920 Principles already had a good claim to be the most influential American book yet translated into Chinese. Classics of American literature, such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851; translated, 1901) or The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876; translated, 1934) (Yin 1987; Lai-Henderson 2015), often took fifty years or more to achieve full translation, but within nine years of its English publication Principles had no fewer than three Chinese translations.

Moreover, Hamilton seeks to “sharply revise” an earlier scholarly consensus (among both Chinese and English scholars) that Taylorism didn’t affect Chinese industrialism until the 1920s and 1930s. He contends instead that the discourse on scientific management–the so-called Xinhai Taylorism–began in China sooner, which was the 1910s. He also argues for Chinese impression and reception of Taylorism as “American” rather than simply “Western.” (I learned from the article that the bulk of the original text was serialized over three issues of the monthly American Magazine, which likely contributed to Chinese attribution of Americanness to the book.) Much of the rest of the article discusses Chinese reception via several prominent intellectuals.

This article is the closest to my own research interest because a number of Vietnamese intellectuals during late colonialism were impressed by Taylorism. I now wonder how much of their exposure to the ideas of scientific management had come from Western sources (i.e., French). And how much, if any, came from Chinese sources.

The last article is closer to Vietnamese Studies: the “rehabilitation” of Republican China in the post-Mao era. Why, asks Qiang Zhang (University of Nottingham), has the authoritarian People’s Republic, even during Xi Jinping’s recent tightening of ideological control, allowed a revival of Republican legacies at popular and intellectual levels? To quote Zhang at length, the CCP’s “official historiography [still] describes the Republican era as a dark, chaotic and oppressive period. At the same time, China still maintains one of the world’s strictest censorship regimes and public discussions are not permitted to deviate from the official line. China is still, in Louisa Lim’s words, the “People’s Republic of Amnesia,” where the state has successfully prevented most of the population from discussing or even remembering sensitive subjects such as the Tiananmen Massacre. Under such censorship, why have views of history that are diametrically opposed to the Party’s orthodox historiography been allowed to appear, let alone thrive?”

You’d have to read the entire article to appreciate Zhang’s argument, but the gist of it is that the post-Mao revival reflects the CCP’s orientation towards interpreting its place in Chinese modernization and nationalism.

I also think that this article carries implications for the scholarship about the former Republic of Vietnam. In the last ten years, we’ve seen a deepening of curiosity and interests in the RVN. In the diaspora, yes, but also and especially in Vietnamese academia. Unless there will be an ideological crackdown, which may very well happen given recent developments within the Vietnamese Communist Party, I expect the interests to grow and expand in the next ten years.

Leave a comment