This is a follow-up to a post from five years ago, when I was promoted to associate professor with tenure. In September 2024, I applied for accelerated promotion to full professor and got it. My experience isn’t representative of American academia since it may be different at other institutions, especially R1 (which mine isn’t). That said, I hope to offer a few insights and pointers about an important marker in academia.

Having come to academia later than most, I felt compelled to fast-track the usual six-year schedule of tenure/promotion:

- August 2013: I began teaching at Pepperdine as a visiting assistant professor.

- August 2015: I began the tenure-track as an assistant professor.

- August 2020: I was tenured and promoted to associate professor.

- August 2025: I became full professor.

Between steps 3 and 4, I applied twice for a five-year professorship. I didn’t get it the first time but applied again the following year and got it. This professorship carries a research fund that has enabled visits to many archives towards my “big book” project.

Shortly before I entered the tenure track, I was offered the choices of a four-year, five-year, or the standard six-year track when applying for tenure. I chose five years. This decision was easy to make. But the next decision, whether to apply for early promotion to full, was a lot tougher to make. I went back-and-forth during Summer 2024, and only decided to go for it six weeks before the application deadline. How come?

The main reason was whether I had “enough” to make a run at accelerated promotion. As a colleague in the know once put it, you can submit an identical application in your fifth year or sixth year, but the Rank, Tenure, and Promotion Committee (RTP) would scrutinize your fifth-year application a lot harder just because it’s a year early. For this reason, it’s essential to gain a clear-eyed idea on whether you have more than enough to justify applying for early promotion. In my mind, I may think I have enough. But RTP members may not look at my record in the same way as I do. It’s always possible that some members may judge it (with good reason) to be insufficient.

Whether you’d decide to apply early, I have three recommendations.

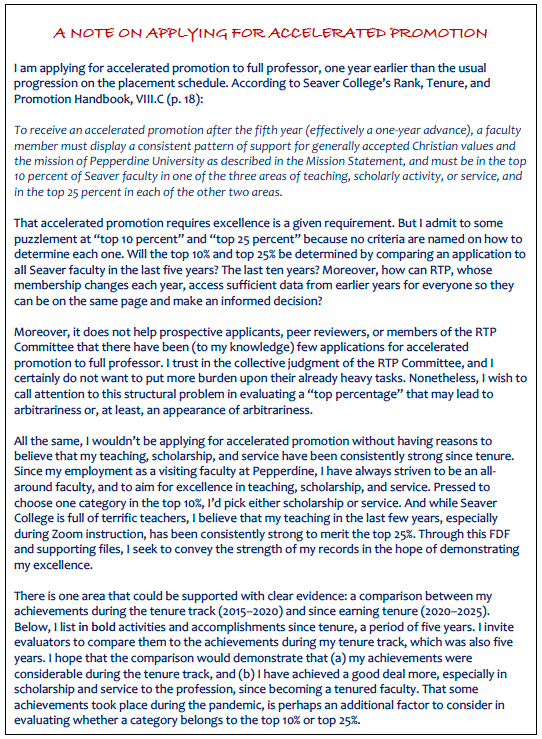

First, evaluate carefully your accomplishments since tenure and measure it according to the best of your knowledge about expectations for accelerated promotion. At Seaver College, the undergraduate school of Pepperdine University, teaching is expected to count for 50% of your accomplishments while scholarship and service for 25% each. Given the weight of teaching at my institution, a middling record on teaching wouldn’t cut it. This is especially true because one-year early promotion expects your record to be ranked among the top 10% in one of those three categories and the top 25% in each of the other categories. (For a two-year early promotion, the expectation is top 10% in all three categories.)

Obviously, I wouldn’t have applied if I didn’t think my record was enough. In particular, I believed that my record of service, especially service to the profession, was in the top 10%. My service to Pepperdine, I thought, wasn’t shabby, but it was the service to the profession that my application should highlight and explain the most. In addition, I recognized that my tenure application didn’t do as good of a job in explaining the significance of my scholarship. (I saw it from RTP’s and the college dean’s tenure letters.) I thought more carefully about how to explain better this time, and ended up characterizing it as “pioneering scholarship.” Lastly, the beginning of my tenure coincided with the pandemic, and I knew that the application would need to explain well my pedagogical accomplishments during Zoom.

My second recommendation is to meet with your department chair and the dean of your college/school. (At my institution, they would be my divisional dean and the dean of Seaver College.) It helps to pick off the brains of the current RTP chair (and/or the previous one). Ask them about their experiences on early promotion, and describe to them your accomplishments since the promotion to associate professor. Generally speaking, these deans and chairs are seasoned with these sorts of things. Having seen plenty of applications for promotion, they should be in a good position to provide helpful feedback. Weigh your record and readjust the aforementioned self-evaluation in light of their feedback, and I think that you get a good sense about what to do.

This recommendation is similar to one of the suggestions from the article in the Chronicle of Higher Education linked above:

Seek advice in your department. Ask your chair and other senior colleagues privately if they think you are ready to make the move, which is a good way to discern if the department will support your goal. If their reaction is lukewarm, you’re unlikely to find stronger support from other reviewers at the college or university level. In sizing up your chances, be sure to gather feedback from not just close colleagues but those whom you suspect may oppose your promotion.

I’ve valued such reaction and feedback. In 2018, I briefly thought about applying for associate professor the year before tenure since I’d be qualified. But a short conversation with my division dean quickly shut down that thought, mainly because my publications weren’t sufficient at that point. On the other hand, the conversations with my (new) division dean, the college dean, and the RTP chair in 2024 convinced me that I should apply for early promotion.

In a similar fashion, after applying for the professorship the first time and not getting it, I met with the vice provost in charge for a better understanding. The meeting was enormously helpful for the next application, which was successful.In retrospect, I should have met with him before the first application–and I’d probably have waited for one year before applying. The point is to do your homework by meeting with others in the know.

My third recommendation is to seek external support for your application. External letters are a requirement at R1 and R2 universities (and possibly some other institutions), and the rules may vary from one institution to another. At Pepperdine, I’d guess that they are required at the Business School, the Law School, the School of Public Policy, and the Graduate School of Education and Psychology. But they haven’t been required at Seaver College. That said, Pepperdine recently earned the R2 designation and I wonder if external letters will be either required or highly recommended in the future.

While they weren’t required, it crossed my mind to seek some external support. In fact, one of my peer reviewers, a seasoned faculty and colleague, suggested to me to ask for a couple of letters of support. His recommendation was perfectly timed because I was thinking the same. I reached out to a number of academics at other institutions: mostly specialists in Vietnam studies and long-time faculty in Great Books programs. Four were affiliated to R1 universities, two at R2, and three at liberal arts institutions. All graciously agreed, and I ended up with five letters focusing on my scholarship and another five on service.

In addition to nine letters from other institutions, one was from a staff at Pepperdine. In fact, she wrote it two years before, testifying to a multi-year kind of service that I gave alongside her and several other staff and faculty. While RTP members understood well service at the university, I wanted to highlight this particular service because it was somewhat atypical. This staff’s letter contributed to that highlight.

I clearly went overboard with ten letters. But I guess I didn’t want to leave anything to chances, ha!

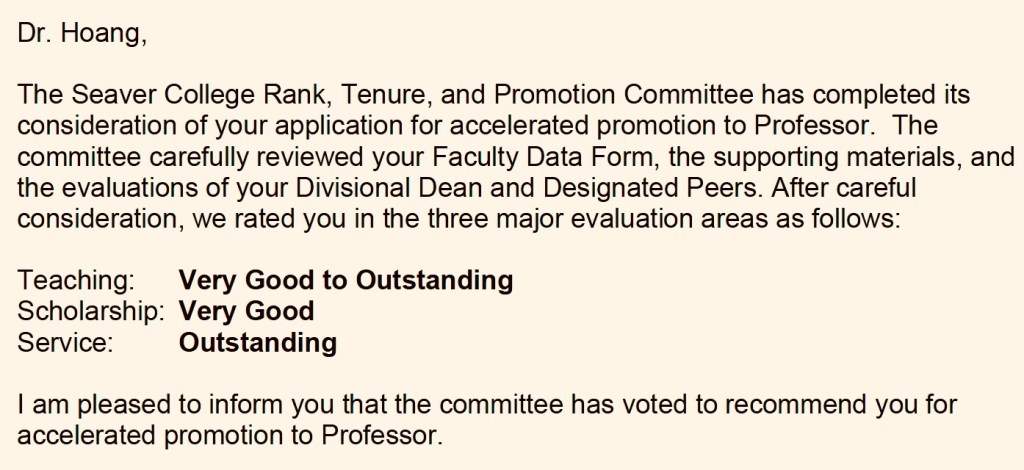

It was during the week of finals that I received a letter from the RTP chair, who informed me that the committee had recommended my accelerated promotion. A similar letter from the college dean came a few days later. Happy news, obviously, and I was extra happy because RTP’s ratings of my teaching, scholarship, and service were higher than my tenure application.

- Scholarship. My tenure application earned the rating of “good to very good,” which was similar to B+. Five years later, this application received the rating of “very good,” which is like A-minus and, therefore, a step higher from before.

- Teaching. The rating of my tenure application had been “very good”; it was now higher at “very good to outstanding.” It was like a raise from A- to a straight A.

- Service. I’d expected this rating to be the highest of three categories, and it turned out to be true. It was “very good to outstanding” for my tenure application. Now it was “outstanding”: i.e., from A to a rare A+.

The ratings further illustrated that “you can’t know for sure what or how committee members are going to evaluate your application.” I’d thought that the rating for scholarship would be higher than that for teaching, but it turned out to be the opposite. One reason, perhaps, is that I was a consistently productive scholar but I haven’t published a monograph. I’d actually anticipated this potential issue and explained why in the application, but I guess that it wasn’t as persuasive as I’d thought. Another reason is that the pandemic created a most unusual situation for teachers. I adapted well to Zoom, and I even wrote in the application that that era was possibly the peak of my teaching. I gave as much evidence as I could to support the statement, and apparently it impressed the committee more than I thought.

An appreciation to all the people involved: RTP members, designated peer reviewers (and any non-designated ones), letter writers, and deans. There’s always a lot of labor about this work, and this case was no exception. Thank you, all!

Lastly, my application included the following long note. I have no idea if it made any difference with the people involved. But it reads like a preface to my application, and writing it was a very good exercise in setting the tone for the application.

My journey would go on regardless of accelerated promotion. That said, earning it has saved me time from applying again this year. Most of all, it helped to keep me motivated during Spring 2025, which was among the toughest semesters I’ve had because of the devastating Palisades and Eaton wildfires in January 2025. It was an entirely different experience, one that I may revisit at some point in the future.

1 Pingback