Belief in God tends to be strong for people living amid warfare. It is hardly a surprise then that prayer finds its way into music written during war. It was surely the case with popular music in South Vietnam.

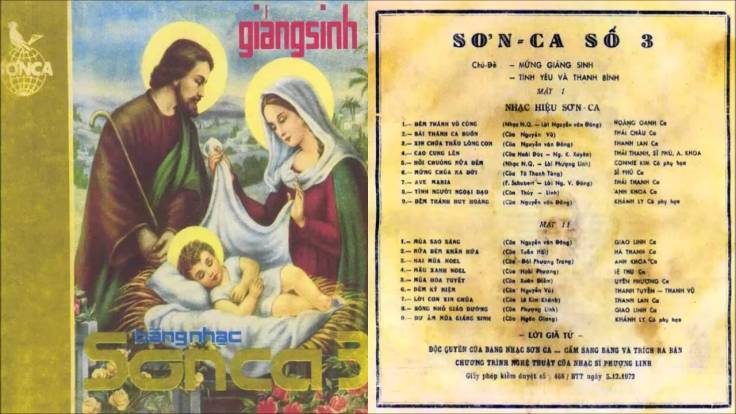

Since this is the week of Christmas, it is worth mentioning that one the most popular South Vietnamese albums is filled with prayer. It is the third album of the fine series Sơn Ca (Birdsong), and the title is simply Giáng Sinh: Tình Yêu và Hòa Bình: Christmas: Love and Peace. It features some of the biggest names in the Saigon music scene at the time: Thái Thanh, Khánh Ly, Thanh Lan, Giao Linh, Lệ Thu, Anh Khoa, etc. (A recording from Elvis Phương would have completed this A-list.)

Made in 1972, not long before the Paris Peace Accords were signed, it reflected the widespread longing for peace after years of vicious warfare. I sometimes wonder if this album helped to set the stage for a creative rush of songs explicitly about peace (that is, not merely against war) during 1973. Perhaps it’s more accurate to consider it as an early part of the creative rush of peace music during 1972-1974.

There are at least a handful of songs from this album that qualify as candidates for a top-ten list. The fifteenth song, for example, is Lời Con Xin Chúa or My Prayer to God. It is perfectly assigned to Thanh Lan and includes this prayer for the refrain.

Cầu xin ơn Chúa xót thương

Thương nhà Việt Nam chinh chiến thê lương.

Lòng con sao mãi vấn vương

Ngày đêm trông ngóng người yêu vắng xa.

I pray for God’s mercy

Mercy on the House of Vietnam and endless warfare.

My heart is so much in love,

Waiting for my love both day and night.

Or, the sixth song closes with a prayer from a soldier. The singer is Sĩ Phú, himself an officer in the Air Force.

Lạy Chúa ban ơn cho Việt Nam bền vững muôn đời,

Hạnh phúc lâu dài xây đắp nền tương lai rực rỡ.

Và từ đây trên khắp nơi nơi, vang tiếng ca non nước thanh bình.

Quên những ngày chinh chiến điêu linh.

Please, God, grant Vietnam permanent stability,

Lasting happiness to build a shining future.

And loud singing for a peaceful land everywhere from now on,

So we can forget the times of warfare and misery.

For this list, however, I decided to go for Đêm Nguyện Cầu because it combines prayer and warfare and especially the Vietnamese nationalist identity more powerfully than anything from the excellent Christmas album. The song, meaning “Night of Prayer” and not “Night Prayer,” is believed to be the very first song from the trio Lê Minh Bằng, whose name derived from its members Lê Dinh, Minh Kỳ, and Anh Bằng.

Anh Bằng is by far the best known of the group, and died only two months ago in Little Saigon, Orange County after running a successful postwar career in ethnic entertainment. Lê Dinh is still alive, having left as a boat person in 1978 and settled in Montreal. Minh Kỳ was the most unfortunate, killed by an unintended grenade during imprisonment shortly after the Fall of Saigon.

So far in this list of ten songs, I have intentionally focused on civilians rather than soldiers. For the last two songs, however, I wish to shift to soldiers, but with a twist in that they speak for all Vietnamese, not merely for soldiers as the case of nhạc lính – soldier music – a category focused on the life and feelings of soldiers.

In any event, this classic has a soldier delivering a prayer on behalf of the nation. He opens the lyrics by addressing his fellow Vietnamese.

Hãy lắng tiếng nói vang trong tâm hồn mình người ơi,

Con tim chân chính không bao giờ biết đến nói dối.

Tôi đi chinh chiến bao năm trường miệt mài

Và hồn tôi mang vết thương vết thương trần ai.

Listen to echoes within our soul.

The righteous heart never speaks lies.

I have been a soldier year after year,

And my soul carries a wound: an earthly, human wound.

Having introduced himself in the last half of the first verse, he elaborates on the combined national and personal sorrow in the second verse.

Có những lúc tiếng chuông đêm đêm vọng về rừng sâu.

Rưng rưng tôi chấp tay nghe hồn khóc đến rướm máu

Bâng khuâng nghe súng vang trong sa mù,

Buồn gục đầu nghẹn ngào nghe non nước tôi trăm ngàn ưu sầu.

When church bells echo in the deep woods.

I fold my hands and listen to the weeping of my soul until it bleeds,

Dolefully I listen to gunshots echo in misty air,

In gloom I weep at the colossal woes of my land.

The refrain moves from self to God. The authors do not use Chúa (Lord), the common Vietnamese term for the God of Christianity, but the older and broader term Thượng Đế: the Almighty or Omnipotent. Anh Bằng was Catholic, but he and his collaborators wanted to speak for all Vietnamese, not only Christians.

Thượng Đế hỡi có thấu cho Việt Nam này,

Nhiều sóng gió trôi dạt lâu dài,

Từng chiến đấu tiêu diệt quân thù bạo tàn.

Thượng Đế hỡi hãy lắng nghe người dân hiền,

Vì đất nước đang còn ưu phiền,

Còn tiếng khóc đi vào đêm trường triền miên.

Oh Almighty, have mercy on this Vietnamese land,

Having endured too many storms for too long,

Having fought and destroyed wicked enemy.

Oh Almighty, please listen to the peaceful people,

Whose country still holds too much misery.

Their weeping sounds move into the long night

The refrain, as elsewhere in the lyrics, keeps the nation at center. The third line could be taken as a reference the proud nationalist trope of fighting foreign enemies in the past.

The final verse ends with a couple of questions, highlighting the soldier’s abiding identity to the nation on the one hand – and, on the other hand, the fact that prayer could go only so far in alleviating the anguish of endless warfare.

Có những lúc tiếng chuông đêm đêm vọng về rừng sâu.

Rưng rưng tôi chấp tay nghe hồn khóc đến rướm máu

Quê hương non nước tôi ai gây hận thù tội tình?

Nhà Việt Nam yêu dấu ơi bao giờ thanh bình?

When church bells echo into the deep woods.

I fold my hands and listen to my soul weep until it bleeds.

My country, my land, who have caused hatred and crime?

My beloved House of Vietnam: when will be peace?

Unlike some of the songs on this list, there is no “definitive” recording of this classic. Below are three recordings before 1975. I’d pick the version by Chế Linh if pressed for only one, partially because it smartly employs a choir at the start and especially for the usual instrumental break.

Terrific too is the recording from Elvis Phương.

There have been other versions from the diaspora since the war, including live recordings for productions created by Anh Bằng’s own company in Little Saigon. But my favorite postwar video is a completely amateur performance, and probably unrehearsed, shown below. It was a gathering of Vietnamese Catholics in Germany six years ago.

The people on stage come from Hamburg and, starting around 1:25, take turn to sing the lyrics to pre-recorded instrumentation. The singing does not always match the music. It is, in fact, pretty terrible. But it doesn’t really matter, since it isn’t individuals but the nation that is at stake here. (It has to do with protests against China in Vietnam earlier that year.) The singers line up and step forward in turn, as if lining up behind a lectern at church to deliver the prayer of the faithful to the Almighty.

This video, I think, illustrates the potentially fearsome power of nationalism. It is an example of the Vietnamese imagined community, extended to the diaspora, even though the war was over four decades ago.

December 24, 2015 at 9:17 am

One fact you have to take into account in your discussion of the song is that it was first published in 1966. I’m not sure that it was the first Lê Minh Bằng song. The problem with the Lê Minh Bằng name is that it camouflages the songwriter – they often used the collaborative name when only 1 or 2 of them had anything to do with the songs creation. Lê Minh Bằng was an entity related to the whole process of writing publishing, recording and promoting their songs.

I think the song has to be view within the window of psy-war. Anh Bằng might have been the master of that approach (this seems very much like an Anh Bằng song). It’s a song of commiseration for the sacrifices made by soldiers and their families. Where I give the songwriters of the south great credit is that they don’t shy away from the describing the suffering that war causes, but they don’t use that suffering as a reason to call for hatred of the enemy.

This is the song that was supposed to have launched Chế Linh’s career.

December 24, 2015 at 3:19 pm

Yes, the entity definitely covers the production process, not merely writing. I’d guess that Anh Bằng was most involved in writing. Apart from LMB, there were some songs from Lê Dinh and Minh Kỳ alone. Maybe the writing collaboration was more evenly divided there…

Your point about psywar is well taken; there could be an entire research project there. AB worked for a time at Nha Chiến Tranh Tâm Lý. LD worked at Saigon Radio for many years. MK was a police officer. Figuring out their individual contribution is daunting, probably impossible. A little easier is research into the culture and ideology behind their music.

December 25, 2015 at 9:47 am

The original recording of this song was performed by Thanh Vũ for Sóng Nhạc records, a label that was run by Lê Minh Bằng. By the way, the Lê Minh Bằng team composed earlier songs using the pseudonymous Mạc Phong Linh, Mai Thiết Lĩnh tandem.