This popular song did not cross my mind at all when I first conceived this list. A passing comment from Jason Gibbs, however, made me think more about it. Later, reading a published comment from the song’s composer prompted its inclusion. It is the least conventional choice for this list, since there isn’t anything overtly about refugees. Yet for reasons below, it speaks subtly about the experience of adjustment to the new land by Vietnamese refugees in the U.S. and elsewhere during the 1970s and 1980s.

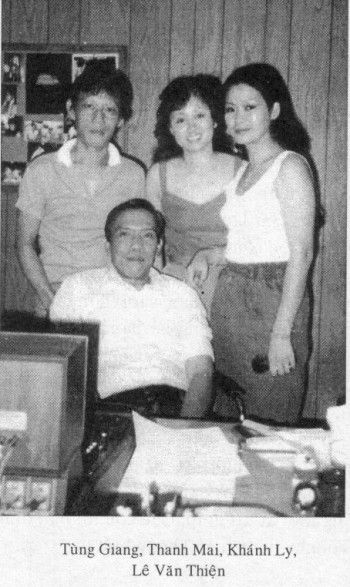

The author is Tùng Giang (1940-2009), a former drummer and album producer in Republican Saigon. One of the major players in the popularization of nhạc trẻ, “youth music” oriented towards musical fashion from Western Europe and America, he came to the U.S. in 1975, thus spending exactly one half of his life in Vietnam and the other half in California.

Tùng Giang didn’t write many songs, and few were recorded. Yet there were at least two hits. One is Biết Đến Thuở Nào, which I translate loosely as When Will I Know?: an upbeat number that used to be very popular at Vietnamese parties and weddings that he co-wrote with his dear friend Trường Kỳ in South Vietnam. (Since the exact title phrase doesn’t appear in the lyrics, the song is also known for the first four words: Phút đầu gặp em or First time we met.)

Here is a recording of the song from The Dreamers, headlined by Phạm Duy’s eldest son Duy Quang. It is a good example of the changing “youth music” in the 1970s that shows large influence by pop and rock music from the U.S. and Western Europe. Note, for instance, the busy percussion during transitions. Or the busier electric guitar during the refrain. Or the original guitar solo, which was unusual because most mid-song instrumental solos at the time merely repeated the notes of first verse.

That was before the Fall of Saigon. Among the first arrivals to California after the war, Tùng Giang was also among the first producers of Vietnamese recording industry in the U.S. He wrote the second hit, this very tune, in the early 1980s. Years later, he was asked if the song had anything to do with romantic troubles. He gave the following response, which went back to 1980 when he was living in the Los Angeles area.

Briefly, the Buddhist-born Tùng Giang was working for the U.S. Catholic Conference in some unspecified media capacity. After work, he headed to Hollywood to study film equipment repair and auto body repair (?) He was doing well, and even took home a number of equipment and cameras to repair for pay, including some “quite old ones.” One day, however, he came to find that the house had been burglarized. His guitar and cassette player were taken, and all the filming equipment. Tùng Giang recalls in the interview,

I sat like a stone and didn’t know what I’ll say to the people at school. They are not going to believe that my house was robbed. Moreover, I am Asian and they might think badly of me. So I quit the classes and didn’t go anymore I was heart-broken, sighing in the night, hence the [first] line in the song: There is sighing at night... I wandered on Sunset Boulevard, saw the baby-faced prostitutes, and wished I could be at peace as they were. Hence the line: Wishing for peace for the small birds… Then I walked past Freeway 101, looked down, and thought of a river, hence the line: Watching myself in the river’s mirror… Such was the background of the song, written with a very sad mindset.

This episode, I think, nicely illustrates the turmoil of adjustment. Vietnamese refugees faced a number of barriers. Some had to do with discrimination and stereotypes (including “positive” stereotypes such as the “model minority,” which has its own complications). Some had to do with having limited English. Some had to do with cultural and economic habits. In this case, Tùng Giang, like countless Vietnamese refugees at the time, was not accustomed to reporting the robbery to the police and requesting a police report so he could show it to the equipment owners. (I suspect that he didn’t have insurance.)

Put it another way, the burglary must have added grief to Tùng Giang’s larger experience of loss, the sorts commonly articulated in refugee music and represented by the first three songs so far: losing Saigon, missing families and friends, and wishing to liberate postwar Vietnam from communism. There were, shall we say, more universal experiences that nonetheless reminded and deepened those losses and desires.

In my second year in the U.S., my three-floor apartment building in southeastern Minnesota, a somewhat run-down place inhabited by newly arrived boat people refugees (plus a couple of elderly white women), was burned down due to a fire from the Chinese restaurant on the first floor. When interviewed by the local newspaper the day after, one of the middle-aged refugees referred to Vietnam and called the fire the second time he lost his home.

Burglaries and fires may occur anywhere and anytime and to anyone: some places, of course, more often than others. But when they occur to refugees as in these cases, they remind and accentuate the already pronounced losses of homeland and people. Short-term immigrant survival could not be understood apart from the larger trajectory of survival from war and postwar realities. I think that this song subtly illustrates the combination of the short-term and the long-term effects.

The lyrics aren’t hard to translate, but neither are they easy. They could have been written by Trịnh Công Sơn in one of his less existential modes – or, conversely, by Ngô Thụy Miên in his more existential ones. Vivid though the robbery episode, the lyrics are meant to convey mood and atmosphere above all, and rather broadly as if several strands of thought simultaneously crossed the narrator’s mind. At the same time, the seeming free association is never out of control. Which, I think, is among the reasons for the wide popularity of this song among many Vietnamese, refugees or not, both then and now.

The first verse sketches out the environment. Nocturnal quiet belies sorrow, albeit of an existential than a political or social kind.

Đêm có tiếng thở dài,

Đêm có những ngậm ngùi.

Khu phố yên nằm,

Đôi bàn chân mỏi,

Trên lối về mưa bay.

There is sighing at night,

There is pity at night.

The quiet town is asleep,

A pair of exhausted feet

Walking over the raining path.

The second verse moves from setting to character, from surroundings to person.

Đêm anh hát một mình

Ru em giấc mộng lành.

Xin những yên bình

Cho loài chim nhỏ

Cao vút trời thênh thang

I sing alone at night,

Sing a lullaby for your sweet dream.

Asking for peace

For the little birds

That fly high over the wide sky.

The refrain continues with the “lullaby” motif, but moves forward to the larger desire for keeping faith in humanity.

Anh ru em ngủ

Không bằng những lời buồn anh đã viết.

Anh ru em ngủ

Này lời ru tha thiết rộn ràng.

Ai cho tôi một ngày yên vui

Cho tôi quên cuộc đời bão nổi,

Để tôi còn yêu thương loài người?

I sing you a lullaby

It’s not as sad as the lyrics I’ve written.

I sing you a lullaby

Here are dear and happy lyrics.

Who will give me a day of peace,

So I’ll forget this stormy night,

And I can love humanity?

The final verse returns to the nocturnal setting and sighing, albeit in the big point that it is just “me and the abandoned world” at this time.

Đêm hiu hắt lạnh lùng

Sâu thêm mắt muộn phiền

Soi bóng đời mình bên giòng sông cũ

Tôi với trời bơ vơ!

The night is cold and lonely,

The eyes are sadder and frailer.

Looking at my life on the river’s mirror:

Me and the lonely world!

There have been many recordings of this song, making it an undisputed standards composed in the diaspora after the war. Below are two videos in addition to the Hương Lan 1985 recording above. One comes from the diasporic vocalist Khánh Hà, recorded probably in the 1990s. She also sings English lyrics, albeit somewhat loosely translated to match notation. The other is an amateur with acoustic guitar; the street sounds tell you that it is in Vietnam. That it is done by, most likely, a non-refugee illustrates its enduring appeal.

This appeal comes partially from the fact that on its surface, the lyrics could have applied to many situations. When placed in the context of place and time above, however, it reveals quite a bit about Vietnamese refugees in their first years in the U.S., Canada, Australia, Germany, etc. Their dreams were not merely about seeing family members and friends still in Vietnam. They also had to do with surviving in the new land on the face of adversity, some of which were as unexpected as (if less dramatic than) the Fall of Saigon they’d experienced not too long before.

March 13, 2016 at 10:54 am

I see the importance of this song being, first of all, that is very well-written. Second, it is a song of a place outside of Vietnam. There is no longing, and no mention of a homeland. Third, it is, as you write, a song that expresses the kind of loneliness or alienation that one actually feels in an alien society. And, to be honest, American society is lonely and alienating for many Americans. The song expresses this without dwelling on the notion of “tha hương” or exile. I think it succeeds as a refugee song because it is, in some way, an American song, or at least a song reflecting American life.

I would translate the song title more literally as “I and the Friendless Sky.”

March 14, 2016 at 4:14 pm

I like the way you put it, that this is “an American song.” It’s definitely not a Vietnam-focused song, and it does seem to hit at a bigger and wider loneliness characterized by American life.

On the other hand, I’m not sure why you’d translate the title as “I and the Friendless Sky” because it doesn’t strike me as that literal. Mind you, it’s not an unacceptable translation. Bơ bơ has range of shades in meaning: bereft, desolate, abandoned, homeless, lonely, etc. “Friendless” may be one such shade, but it’s closer to the margin than the center of this range.

A frequent use of bơ vơ has to do with funerals. When growing up, I heard women weep at funerals and cry out something along the line, “Anh ơi, anh ra đi bỏ vợ con bơ vơ…”: Alas, you depart and leave your wife and children bereft… This usage is still common in the context of death or abandonment or both: e.g., Mẹ bỏ đi, bốn anh em bơ vơ sau ngày tang cha. http://www.phapluatso.com/me-bo-di-4-anh-em-bo-vo-sau-ngay-tang-cha.html

One of the most famous songs recorded by Chế Linh and Thanh Tuyền is, of course, Tình Bơ Vơ. It too has to do with death and bereavement.

Cuối cùng là tình bơ vơ

Cho anh xin một đêm trăn trối…

Em khóc cho duyên hững hờ

Anh chết trong mộng ngày thơ.

Another common shade in usage is the experience of homelessness, literally and/or figuratively. I believe bơ vơ shows up in Truyện Kiều many times, and perhaps “friendless” may apply to one or more instances there: e.g., Tự thương thân khổ bơ vơ / Kiếp người lưu lạc bao giờ mới thôi. But other meanings apply elsewhere: e.g., Trời đông vừa rạng ngàn dâu, / Bơ vơ nào đã biết đâu là nhà! In this case – and even in the first example – bơ vơ has to do with “homeless.” I think that it applies to people (or a lack of) for most of the times, but sometimes it conveys more than just that.

As for “Tôi” in the title, I opted for “Me” instead of “I” because the phrase doesn’t have a verb as it ends the lyrics. It’s more like a statement: All left now is “me and the lonely world” (or, if one prefers, the lonely sky.)